Federal programs such as Medicaid, Social Security, and food assistance (e.g., SNAP) have strict eligibility rules that are often based on income or work history. For immigrants, there’s typically another requirement: an eligible immigration status.

Since 1996, access to many federal programs has been limited to citizens and people that the law defines as “qualified aliens” — such as green card holders, refugees, and asylees. In 2025, a series of changes, most tied to legislation known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), modified access for several groups.

Many immigrants living in the US are here with the government’s knowledge and permission. This includes foreign-born naturalized citizens, people with green cards (also known as lawful permanent residents), those granted humanitarian protections like people with refugee or asylee status, work and student visa holders, and individuals who are waiting for a decision on their application for asylum. It also includes recipients of DACA, who came to the US as minors and currently have temporary protection from deportation.

Though the aforementioned groups are legally allowed to be in the United States, not all are eligible for government benefit programs. In general, only people authorized to be in the US for an extended period of time, such as green card holders and sometimes refugees and asylees, are eligible. Immigrants with temporary or pending statuses, even if they’re authorized to live or work in the US, are typically excluded.

People who entered the US without authorization or who overstayed a visa, referred to here as “unauthorized immigrants,” are not lawfully present under federal immigration law. Typically, they are not eligible for government benefits. The main exception is access to public K–12 education, which children can receive regardless of their immigration status.

Can states offer additional healthcare coverage to immigrants?

In some cases, yes — though the options vary depending on the state and the program. Federal rules determine who can receive Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and other public health coverage programs. But states can expand access to certain immigrant groups who don’t meet all federal requirements.

One example is Emergency Medicaid, which every state offers. Federal law requires hospital emergency departments to treat anyone in an emergency, regardless of immigration status or ability to pay. To help cover those costs, states can use Emergency Medicaid — a limited version of Medicaid for people who would otherwise qualify but don’t meet immigration status requirements. It does not cover ongoing or preventive care. In 2023, the federal government spent $2.8 billion on Emergency Medicaid, less than 1% of Medicaid spending, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

States can also expand program coverage beyond emergencies. A 2009 federal option lets states waive the five-year residency requirement for lawfully residing children and pregnant individuals, allowing them to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP right away if they otherwise qualify. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 25 states and Washington, DC, waive the Medicaid wait for both groups, nine cover only children, and one covers only pregnant people.

Some states go further, using their own funds to offer Medicaid-like coverage to people who are ineligible for federally funded Medicaid, including people within the five-year wait, with temporary or pending status, or without legal status. These state-funded programs vary widely in who they cover and what services they provide. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act could mean a reduction in the federal Medicaid matching rate for states offering this type of coverage, increasing the state’s share of program costs.

How often do immigrants use public benefit programs?

In 2023, an estimated 22.8 million people living in the US were not citizens. That’s about seven in every 100 people. This group does not include naturalized citizens but includes all other immigrants, from green card holders and refugees to DACA recipients and unauthorized immigrants. Immigration law refers to this group as “aliens,” though they are also known as noncitizen immigrants.

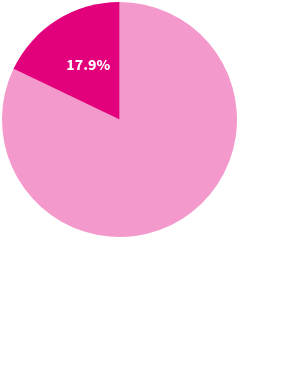

These noncitizen immigrants made up between 2% and 6.8% of beneficiaries in the major government assistance programs. Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people aged 65 and older, had the lowest share of noncitizen participants; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), had the highest.

Because noncitizens are a smaller share of the US population than citizens, it’s useful to compare program participation rates relative to each group’s size. In 2023, noncitizens participated in each of these programs at a lower rate than citizens. (TANF was the exception, with rates for both groups at 0.6%.)

One reason for this could be eligibility rules: immigration status prevents many noncitizens from accessing certain programs. Other requirements — such as income, age, disability, or work history — apply to everyone.

Do immigrants pay taxes?

Generally speaking, yes. Like US citizens, noncitizen immigrants pay sales tax when they buy goods and services, and they contribute to property taxes, either directly as homeowners or indirectly through rent. They also pay other state and local taxes in the course of daily life. Income taxes are more complicated, but many noncitizen immigrants also pay them.

Immigrants who are authorized to work — meaning they have permission from the federal government to be employed — have a Social Security number (SSN), so they typically use the same tax system as US citizens. Employers withhold payroll taxes from their wages, and most workers file annual federal and state tax returns. These payroll taxes also help fund Social Security and Medicare.

Because US tax law is based on income rather than work authorization, noncitizen immigrants who earn money in the United States are generally required to pay income taxes, even if the work is unauthorized. IRS guidance specifies that workers must report income from all sources — including illegal activities.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that around half of undocumented immigrants pay federal, state, and local taxes. Some use false or borrowed SSNs to gain employment, which results in payroll taxes being withheld in the same manner as a legitimate SSN. Other people work as independent contractors (where no taxes are withheld but income may still be reported to the IRS), or in cash-only jobs where earnings are generally not reported. Some people without work authorization file tax returns if their income has been reported to the IRS or if they believe it could help their case in a future immigration proceeding.

Immigrants who do not qualify for an SSN — including some unauthorized workers, students, and people with certain temporary visas — often use an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) to file a tax return. The IRS issues ITINs for tax purposes only; it does not grant work authorization or make someone eligible for Social Security benefits. In 2022, more than 3.7 million tax returns were filed with at least one ITIN, reporting about $18.2 billion in income tax before credits.

How does the OBBB impact program eligibility for immigrants?

The OBBB, signed into law in July 2025, changed which noncitizen immigrants can access certain public benefit programs. Eligibility for programs including SNAP, Medicaid, and Medicare is now limited mainly to green card holders, with some exceptions. People who had previously qualified under temporary protections or humanitarian statuses are no longer eligible.

Other recent policy changes have come from separate legislation and agency rules. One example is a July Department of Health and Human Services ruling that reclassified several programs — including Head Start, a federally funded early childhood education program for low-income families — to make them available only to “qualified aliens.” These programs had previously been open to eligible participants regardless of immigration status.

Not all of these eligibility shifts will take effect immediately. Some begin this year, while others will be phased in over the next several years.

Immigration and immigrant rights remain frequently discussed in public and policy circles. Eligibility rules, tax contributions, and benefit use are often discussed separately, but shape one another in ways that affect millions of people. We at USAFacts aren’t advocating for any policy but hope that by collecting this data directly from government sources and arranging it for easy comparisons, we can ground benefit debates in facts.

Keep exploring visualizations

Page sources

Congressional Research Service

Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview and 5 others

Census Bureau

American Community Survey (ACS)