How many homeless people are in the US? What does the data miss?

The total homeless population in the US rose 18% from 2023 to 2024.

Around 23 out of every 10,000 Americans — 771,480 people — experienced homelessness in January 2024 according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) annual point-in-time report, which measures homelessness across the US on a single night each winter. That’s an 18% increase from the same report in 2023.

How is homelessness defined?

The HUD’s definition includes both sheltered and unsheltered people. Sheltered people are living in emergency shelters, transitional shelters, safe havens serving people with severe mental illness, or hotels/motels. Unsheltered people live outdoors, in cars, in abandoned buildings, or in other places unfit for human habitation.

People staying with friends are considered homeless if they cannot stay longer than 14 days.

Who is homeless in America?

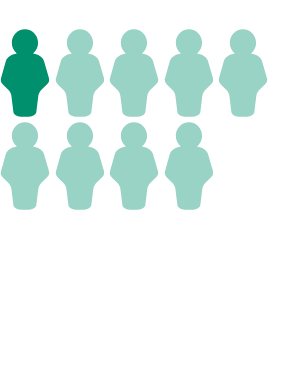

Over 240,000 homeless Americans — 31.6% of the homeless population — identified as Black, African American, or African in 2024. This was the largest population of unhoused people. This same demographic made up 13.7% of the US population in 2023. Hispanic-identified people, who were 19% of the national population, were 31% of the homeless population.

Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders had the highest rate of homelessness at 126.5 per 10,000 people in that racial category. These rates could be partially a result of the high cost of living in Hawaii — in 2023, it was among the states with the highest rates of owners and renters who were housing-burdened, people spending more than 30% of their incomes on housing.

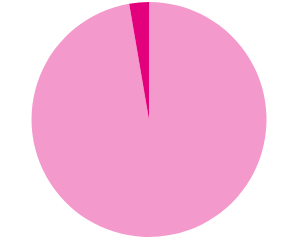

In 2024, 59.6% of homeless people were cisgender men and 39.2% were cis women. Around 1.2% of homeless Americans were transgender, nonbinary, questioning, or reported more than one gender. Per 2024 government survey data, 50.3% of all US adults identified as cisgender women, 47.1% as cisgender men, 1.0% as trans, and 1.7% as otherwise outside of the gender binary.

The US also has a homeless veteran population, though this group is declining — from 73,367 in 2009 to 32,882 in 2024. The overall veteran population has also been getting smaller, from 21.9 million in 2009 to 15.8 million in 2024.

Programs such as the HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing program help veterans find permanent housing and access healthcare.

How has the homeless population changed over time?

The total homeless population went down generally from 2007 to 2022 before rising 12% in 2023 and another 18% in 2024. The US Interagency Council on Homelessness attributes the current rise to inadequate systems for managing affordable housing, wages, and equitable access to health care and economic opportunity. According to the Council, people who experience homelessness have a life expectancy of 50, compared to 77 for the average American.

Homelessness looks very different across states and cities and towns, and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that rising rent and job losses contribute to homelessness. Policies regarding encampment and shelter restrictions, as well as situations that change from person to person (such as poverty and experiencing domestic violence) also affect homelessness rates.

How is this data collected, and who does it miss?

HUD has separate homelessness counts for sheltered and unsheltered people. Both counting methods have flaws and likely lead to underestimates.

Unsheltered people

An annual point-of-time count of unsheltered people (an unduplicated count, on a single night, of all the homeless people in the US) happens in the last week of January. HUD chose January because shelter use is highest in this month, so it expects a more accurate count of people who are truly unsheltered long-term, rather than those who use shelters intermittently.

Localities approach point-in-time counts differently. Many use a public places count, where volunteers and workers visit locations where homeless people are believed to congregate. Police officers are sometimes used to help identify locations or access potentially dangerous areas like abandoned buildings.

There are several drawbacks of counts in public places. First, they rely on a list of places where homeless people are known to gather, which could lead to an undercount. People living in cars or checking in and out of motels may be missed. People may also deliberately hide to avoid the count, and some people may be less forthcoming about their situations when faced with a police presence.

Other localities take a service-based approach, basing their counts on use of food pantries, soup kitchens, social service agencies, and other non-shelter services. This requires significant screening to make sure only homeless individuals are counted and misses the people who never use these services.

Sheltered people

Homeless people in shelters are easier to track because they more consistently interact with government resources. The Homeless Management Information Systems track the characteristics of people using services such as emergency shelters and transitional housing. Some localities also supplement this data with surveys.

Sheltered counts offer more consistent data but aren’t without challenges: Rural homeless services providers struggle with understaffing and poor technology infrastructure, communication, and transportation over large geographical areas. Sheltered counts also exclude people staying with family or friends, children living in emergency foster care or detention facilities, or adults in criminal justice facilities.

Counting homeless individuals is difficult, but a 2020 report from the GAO recommended more regular quality checks of data collection methods as a way to improve accuracy.

Read more about the states and cities with the highest homelessness rates, and get the facts every week by signing up for our newsletter.

Keep exploring

Page sources

Department of Housing and Urban Development

2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress

Department of Housing and Urban Development

Point-In-Time Methodology Guide