Ask an Analyst: Putting White House construction in context

Go behind the scenes with our team as we find and make sense of the numbers.

You may have heard that the White House is getting a new ballroom. According to the Trump administration, this construction project “echoes the storied history of improvements and additions” that previous presidents had made to the White House.

I wasn’t terribly familiar with that history, so I found myself wondering what counts as a normal change to one of the most famous buildings in the country. More specifically, I wanted to know whether the proposed price tag — currently estimated between $200 to $400 million — is typical for a major White House renovation.

At USAFacts, we usually answer questions with data sourced directly from the US government. Most of the time, that means I’m downloading a spreadsheet and digging in. But sometimes, the information I need is scattered across reports, budget documents, and historical records, and I have to piece it together myself to build a usable dataset.

This was one of those times.

Keep reading to see where that search led. Or, jump over to see what I created once I had the data I was looking for.

First stop: the budget of the US government

When I want to understand how the US government spends money, the first place I usually look is the Office of Management and Budget’s Budget of the US Government. It’s the most comprehensive view of presidential budget proposals, along with detailed supporting documents released each fiscal year.

I found my first real lead in the Technical Supplement to the 2026 budget.

In that document, two line items under the Executive Office of the President (EOP) stood out:

- “Executive Residence at the White House” for the “care, maintenance, and operation of the Executive Residence” (obligated $16.1 million for FY 2026)

- “White House Repair and Restoration” for the “repair, alteration, and improvement of the Executive Residence at the White House” (obligated $2.5 million for FY 2026)

At first, these seemed like they might offer a baseline for how much the government regularly spends maintaining the White House. But it quickly became clear that this budget only tells part of the story.

What the budget did (and didn’t) answer

Both line items I found apply only to the Executive Residence — the central portion of the building where the first family lives — and don’t include the East or West Wings. The spending they cover is also mostly routine maintenance: painting, plumbing, electrical work, and the like, not large-scale renovations that substantially change the building.

Even so, seeing over $18 million allocated to routine maintenance in a single year helped put a proposed $200–$400 million project in perspective. After all, related data, even when it’s not exactly what I'm looking for, can sometimes provide valuable context. So, I decided to look at how those maintenance and restoration costs have changed over time.

That’s where the next limitation showed up. For a few years in the early 2000s, an accounting change folded these line items together with other parts of the Executive Office of the President budget. The funding was still there, but it was no longer possible to separate how much of the total EOP budget went to White House maintenance. With no clean workaround using public data (and since this wasn’t the core question I was trying to answer) I left those years as gaps in my spreadsheet and kept moving.

Maintenance of the Executive Residence has gotten more expensive over the past century, after adjusting for inflation

Annual net outlays by fiscal year, adjusted to FY 2025 dollars

Why I had to change approaches

As I dug further, a bigger issue loomed. Funding for major White House construction projects doesn't typically come out of the EOP budget.

Since 1949, the General Services Administration has overseen the maintenance and renovation of historic federal buildings, including the White House. The surrounding grounds, however, fall under the National Park Service. But those agencies typically report spending in aggregate, covering hundreds or thousands of buildings or acres of land at once. It’s rare for costs associated with the White House to be broken out separately.

In a few cases, I found references to the cost of small phases of major restoration projects, but the information was scattered and far from comprehensive. By this point, it was clear that the federal budget alone wasn’t going to give me a reliable way to compare the proposed ballroom to previous large-scale changes to the White House.

I needed a different approach.

Looking beyond the budget

Around the time I started working on this project, the White House and several major news outlets began publishing timelines of historic renovation projects that took place at the White House. While none of these lists claimed to be exhaustive, they consistently highlighted the most notable and expensive projects of the past century.

Because of our data and editorial guidelines at USAFacts, I couldn’t use media reporting as an official source, but these timelines gave me something just as useful: a starting list of projects that were widely understood to be significant. From there, my goal was to see whether I could track down official government documentation for the cost of each project.

To keep the scope manageable, I narrowed that list to projects involving the White House structure itself and excluded changes to the grounds, like tennis and basketball courts and the Rose Garden.

Searching for government records

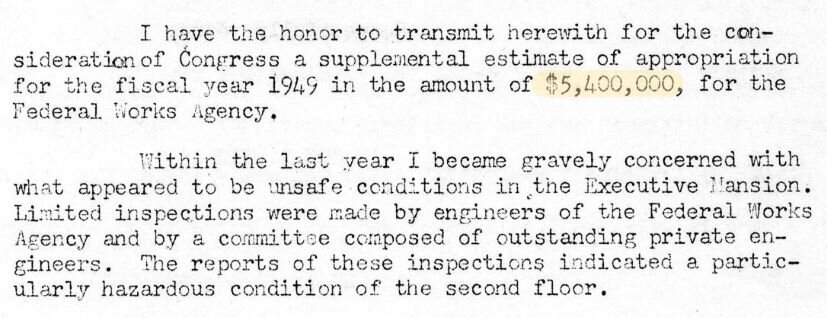

From there, I spent a lot of time searching digitized records from the National Archives. Some projects were relatively easy to document. The Truman-era renovation of the Executive Residence, for example, is well covered in the historical record, and I was able to find a 1949 White House press release requesting $5.4 million from Congress (around $72 million today) fairly quickly.

From President Truman to the Senate on February 16, 1949.

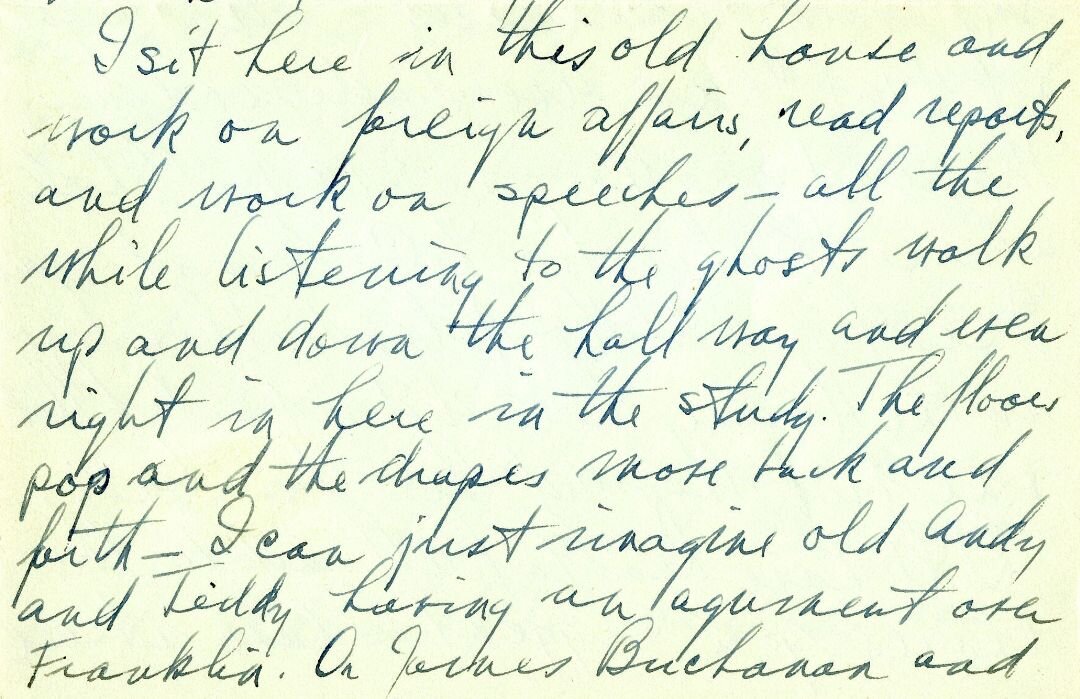

(A letter from President Truman to his wife, describing the White House as haunted when it was really just structurally unsound, was a harder-to-find bonus.)

From President Truman to his wife, Bess, on June 12, 1945. Ghosts or a building that needs some serious maintenance?

Other projects took much more work to find. Not all archival records are digitized, searchable, or consistently labeled, especially for older projects. Still, I relied on a mix of Congressional Records, presidential press releases, and documents in presidential libraries, reading through anything that might reference construction, funding requests, or private donations.

What I could find — and what I used

One recurring challenge: for many projects, I couldn’t find consistent, definitive final costs in the historical record. What I could usually find was either the original amount requested from Congress (if the work was federally financed) or the amount raised through private donations (if it was privately financed).

So, that’s what I ultimately used.

While requested or raised amounts aren’t always identical to final expenditures, they do provide a reliable sense of scale, especially when comparing projects across decades. They also allowed me to make a direct comparison to the still-unfinished ballroom project, the total cost of which won’t be known for a while.

What the records revealed about private funding

Among the projects I was able to document, I found only two clear cases where structural changes to the White House were privately funded. One appears in a 1933 Congressional Record, documenting the acceptance of private donations to build a swimming pool for President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

![An excerpt from a telegram from Fred Pasley which was read aloud to Congress March 27, 1933. The relevant sentence reads "The [swimming pool] fund now totals in cash $13,216.93, and the grand over-all total, which includes services and equipment, $22,656.90." It goes on to describe that the fund came largely from small (less than $1) donations from people nationwide.](https://cdn.builder.io/api/v1/image/assets%2F0b9e002c2ba04655a10a2d191e448df9%2F71433d86d87d462fa2305bc0c2f09366)

An excerpt from a telegram from Fred Pasley, a “newspaperman in New York” which was read aloud to Congress March 27, 1933.

The other comes from a White House memo preserved in the Gerald Ford Presidential Library, describing the privately funded construction of a one-lane bowling alley during Richard Nixon’s presidency.

![An excerpt from a letter from Helen Smith, White House press secretary, on August 14, 1973. The relevant section reads "The bowling alley under the North Portico has been donated by three ananomous [sic] contributors. The amount these donors will reimburse the government for is $40,698.95."](https://cdn.builder.io/api/v1/image/assets%2F0b9e002c2ba04655a10a2d191e448df9%2Fba7d0cb3917f4990a1de0eb36478ad77)

An excerpt from a letter from Helen Smith, the First Lady's press secretary, dated August 14, 1973.

When it comes to funding big White House projects, private funding appears to be rare.

How complete is this picture?

In total, I was able to find official government documentation for 10 of the 14 White House renovation projects most commonly referenced over the past 100 years.

Privately funded White House renovations have typically involved less than $1 million

By fiscal year that the funding was requested or funds were raised, adjusted to FY 2025 dollars

There were four projects where I couldn’t definitively locate standalone cost documentation tied directly to the White House, despite extensive searching:

- The 1934 West Wing expansion

- The 1942 East Wing addition

- The 1969 Press Room addition (fun fact: it was built on top of FDR’s privately funded swimming pool!)

- The 2006 Press Room renovation

I had a decision to make: continue spinning my wheels on these last projects, or, accept that there may not be a readily available source and continue without them. To make that decision, I needed to know if any of the missing projects were expensive enough to actually change my understanding of everything else I’d found. If one of these turned out to be a massive renovation hiding in the record, that would’ve been a pretty strong signal that I needed to keep digging and likely file some formal records requests.

I created a “best guess” for each project’s financing based on the most credible evidence I could find. These aren’t official figures, and I didn’t include them in my final dataset. But they did help me decide how to move forward.

1934 West Wing expansion

Best guess: $325,000 ($7.8 million today). I couldn’t find any explicit cost details, but one line item in the 1936 federal budget caught my eye: an estimated $325,000 in fiscal year 1935 for an “addition to executive office” under the National Park Service. I wasn’t able to definitively confirm that this refers to the West Wing expansion, but the timing and description seem to line up fairly closely.

1942 East Wing addition

Best guess: Under $3.4 million ($68 million today). The East Wing expansion happened alongside the construction of a presidential emergency operations bunker during World War II, which already makes it a bit of a special case. Research summarized by the National Trust suggests the project was likely funded through a national-defense appropriations statute that provided about $3.4 million for public buildings in the Washington, DC area, among many other things. That’s roughly $68 million in today’s dollars.

Even at the high end, though, that figure reflects a much broader set of wartime construction costs and it isn’t possible to tease out what portion, if any, was specific to the White House itself.

1969 Press Room addition

Best guess: $574,000 ($5 million today). Contemporary reporting places the cost of converting the former Roosevelt swimming pool into a press briefing space at around $574,000, or under $5 million in today’s dollars.

2006 Press Room renovation

Best guess: $8 million ($13 million today) Reporting at the time put the cost of this renovation at around $8 million, with around $6 million funded by the federal government and $2 million coming from the press.

Even under fairly generous assumptions, all of these missing projects seem to be much smaller than the ballroom renovation and other expensive projects for which I had found official sources. That gave me confidence that, while the historical record isn’t perfectly complete, the gaps here aren’t hiding anything big enough to overturn the broader pattern I was seeing.

That said, I would still love to update my dataset and article with these official values, so if you know where I can find official records for these projects, please send us an email at [email protected].

The final data

Given what I pulled together, I feel fairly confident saying that most structural renovations over the past century have been relatively modest in scale (under $10 million or so), even after adjusting for inflation. A small number of projects, specifically the 1949 Executive Residence renovation, the 2008 modernization of the East and West Wings and the current East Wing ballroom construction stand out for their cost.

And while privately funded renovation projects have happened in the past, they are relatively rare. So, to put it all in context: the current ballroom project is on the costlier end when it comes to White House renovations, particularly privately funded ones.

Few White House renovations have cost more than $10 million in the past 100 years

By fiscal year that the funding was requested or funds were raised, adjusted to FY 2025 dollars